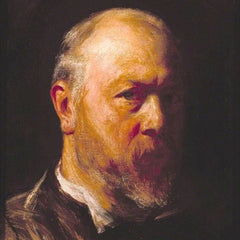

John Pettie RA HRSA (1839-1893) was a well-admired Scottish painter of portraits, history and ‘costume’ genre.

Pettie was born and spent the first thirteen years of his life in Edinburgh, before his family moved to East Linton in Haddingtonshire. Here, his father Alexander Pettie purchased the village shop, from which he supplied an array of disparate goods to the local village folk. Evidently with aspirations that his son would follow suit, his father tasked the young lad with various errands, such as fetching stock from the cellar or storeroom. However, much to his dismay, he often discovered him covering lids of boxes with surreptitious sketches, oblivious to the task at hand.

From an early age, he was imbued with a free spirit and captivated by dramatic fiction, such as the books of Sir Walter Scott. These were particularly appealing for their romance, intrigue and masterful portrayal of character, and would form the basis of several of his works.

Keen to impress his parents, he produced numerous portraits of family members in crayon, along with copies (interpreted in his own way) of contemporary paintings, until his mother finally capitulated and took him to Edinburgh to meet James Drummond RSA. Drummond was well-versed in such introductions and initially discouraged the downbeat young aspirant from his artistic pursuits, stating to his mother, "much better make him stick to business". However, upon perusing an eagerly assembled parcel of drawings, paused, and exclaimed, “Well, madam, you can put that boy to what you like, but he'll die an artist!"

In 1855, Pettie enrolled at the Trustees’ Academy in Edinburgh where he studied under Robert Scott Lauder, who would become a key influence. It was a particularly strong assemblage of students, which included Sir William Quiller Orchardson RA (1832-1910), William McTaggart (1835-1910) and George Paul Chalmers RSA (1833-1878). By all accounts, Lauder was an excellent teacher, offering a framework of ideas without stifling individual creativity. One of his key tenets, impressed upon his students, was to consider a group of figures rather than each one in isolation. Generally, students are put through their paces in life drawing classes and taught to observe and evaluate light as it falls upon a single form. But Lauder taught them to view a collective as a single entity, thus teaching them ‘to see’. Many of the artists who studied with him would later be regarded as the ‘Edinburgh School’ and known for their alternative approach to genre painting. Nearly all of them were from working-class backgrounds.

Aside from his tuition, Pettie also found various delights at the Scottish National Gallery, which offered a seemingly endless assortment of old masters, including works by Van Dyck, Gainsborough and Raeburn. One can imagine him furiously sketching alongside a fellow student, eager to discuss the nuances of a particular hand. He was awarded several prizes during his time in Edinburgh.

From here, now furnished with the skills to complement his enthusiasm, his path was established and he debuted at both the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) and Royal Academy within two years. At the RSA, he exhibited ‘A Scene from the Fortunes of Nigel’, one of the many subjects inspired by Sir Walter Scott.

From the very outset of his career, he astonished both teachers and students with his vigorous approach and tireless attitude. His energy was peerless, and he’d work in a ‘white heat’, of ‘strenuous effort’, with little in the way of preparation or preliminary sketches. This reduced the chance of his finished works ever becoming laboured. Via a fair amount of improvisation, he retained the spirit of a piece.

John Pettie, The Gamblers Victim (1869)

John Pettie, Proposal (1869)

In his biography, he’s quoted as stating, "I felt about colour then like a boy looking at all the bright bottles in a sweetshop window, that it was something to be bought when I had saved up a penny worth of drawing”. This speaks volumes about his qualities as a proficient draughtsman but also underpins his triumph as a colourist. We’ve included further information about his methodologies in our directory.

Following his success at the Royal Academy, he moved to London, where he joined his friend, William Quiller Orchardson. Together with Tom Graham and George Paul Chalmers, the Edinburgh alumni remained closely associated for the remainder of their careers.

As referred to above, the Scotsmen tended to approach genre painting somewhat differently from their English contemporaries, as they provided space for their figures to ‘breathe’. Oftentimes, Victorian scenes were a little overcrowded with emphasis placed upon the artist’s virtuosity in capturing every detail of an extensive interior. But with the Scots, they avoided (or sometimes even removed) any element that didn’t contribute to the overall narrative. With clever use of light and shade, they alluded to an ‘atmosphere’.

John Pettie, Bonnie Prince Charlie Entering the Ballroom at Holyroodhouse

John Pettie, Two Strings To Her Bow (1882)

Aside from his scenes, Pettie was also an accomplished portraitist and produced various depictions of his contemporaries. His portrait of the artist James Campbell Noble is currently at the National Galleries of Scotland.

While working at the peak of his abilities, he was tragically struck down by illness and died at the age of 53.

“One remembers the big, powerful hand, ‘too clumsy for water-colour,’ but ever ready to give the grip of hearty friendship; his bluff and vigorous presence; his rough eloquence; the vigour with which he spoke of art, and denounced what to him seemed false or foolish; his ready sympathy with all who needed help; his kindly smile; his infectious humour; the merry twinkle of his eye.”

Martin Hardie.

He’s represented in numerous public collections, including at the British Museum, Royal Collection Trust, Tate Britain, National Portrait Gallery, Royal Academy of Arts, Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture, Ashmolean Museum, and the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Exhibited

Royal Academy, Royal Scottish Academy, Royal Society of British Artists.

Public Collections

British Museum, Royal Collection Trust, Tate Britain, National Portrait Gallery, Royal Academy of Arts, Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture, Aberdeen Art Gallery, Aberystwyth University School of Art Museum and Galleries, Ashmolean Museum, Bristol Museum & Art Gallery, Edinburgh College of Art (University of Edinburgh), Ferens Art Gallery, Gallery Oldham, Glasgow Museum, Harris Manchester College, Hospitalfield, Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds Museums and Galleries, Leicester Town Hall, Manchester Art Gallery, McLean Museum and Art Gallery, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, Middlesbrough Town Hall, National Galleries of Scotland, National Museum Cardiff, National Trust for Scotland at Fyvie Castle, Paisley Museum and Art Galleries, Perth Art Gallery, Royal College of Music, Royal Holloway at the University of London, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum, The Fitzwilliam Museum, The Hunterian at the University of Glasgow, The Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery at the University of Leeds, The Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum, Touchstones Rochdale, University of Edinburgh, Walker Art Gallery, Westminster College at Cambridge, Williamson Art Gallery & Museum, Wolverhampton Art Gallery, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Baltimore Museum of Art.

Timeline

1839

Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, to Alexander Pettie and Alison Pettie.

1841

Lived in Edinburgh with his family.

1851

Lived in Edinburgh with his family.

1852

Moved to East Linton, Haddingtonshire.

1855

Enrolled at the Trustees’ Academy in Edinburgh, where he trained under Robert Scott Lauder with William Quiller Orchardson, J. MacWhirter, William McTaggart, Peter Graham, Tom Graham and George Paul Chalmers.

1858

Debuted at the Royal Scottish Academy with ‘A Scene from the Fortunes of Nigel’ and two portraits.

1860

Debuted at the Royal Academy with ‘The Armourers’.

1861

Lived in Edinburgh with Robert and Margaret Frier, his uncle and aunt, along with various cousins and a servant. Occupation recorded as ‘Historical Painter’.

1862

Moved to London.

Travelled to Brittany with Tom Graham and George Paul Chalmers.

1865

Married Elizabeth Ann Bossom in Hastings, Sussex.

Moved to Regent’s Park, London.

1866

Elected an Associate of the Royal Academy.

1867

Travelled to Italy, visiting Venice and Rome.

1869

Moved to St John’s Wood Road, London, where his studio was built into the house.

1871

Lived in St John’s Wood, London, with his wife, children, mother, sister, brother and staff.

1874

Elected a member of the Royal Academy.

1881

Lived in St John’s Wood, London, with his wife, children and staff. Occupation recorded as ‘Artist Historical Painter’.

1891

Lived in Hampstead, London, with his wife, three children, and staff.

1893

Died in Hastings, Sussex.

Reviews

Echo, London

"’The Hour,’ by Pettie, R.A., shows a Spanish lady going to keep an appointment. She has an intense desire to be punctual, so that we can see that her errand is not to meet a laundress, but a lover. The color, as is usual with Mr. Pettie, is rich and powerful.”

The Academy

“Mr. Pettie has a very telling work in Rob Roy, and a natural and agreeable one in The Laird, strolling through: his harvest-fields. More important than either of these is The Hour, which shows a Spanish lady of high degree, with a black mask dangling from her left hand, descending the lordly staircase to keep an assignation as the sun sinks low in the west, and strikes full upon her face—a face of rather sinister handsomeness. The pitch of execution in this picture is high throughout, and most specially so in the red dress associated with the black mantilla, Mr. Pettie has adhered to the trying rule, ‘Be bold, be bold;’ nor do we think he has in this instance laid himself open to the censure implied in the final caveat, ‘Be not too bold.’”

Martin Hardie’s Biography

“Two more Academy pictures of 1878 call for mention. One of them, ‘The Hour,’ is a picture that, more than anything else by Pettie, shows the influence of Phillip. It seems to have been painted with an inspiring fervour that swept him into a passionate grandeur of form and colour. To Pettie, as to the early Romanticists of nineteenth-century France, a beautiful piece of red cloth was an artistic pleasure, a protest against the grey and dull, just as Victor Hugo's passionate phrases were a revolt against the rigid declamation of Corneille and Racine. In ‘The Hour,’ as in ‘Ho ! Ho ! Old Noll’ and ‘The State Secret,’ he glories in red, handling a scheme of colour whose richness and fulness is gained by impetuous and unlaboured brushwork. The lady who descends the stair with domino in hand, to keep her assignation, is of a Spanish type, and her dress is all of red, covered with black lace. It is a red that gives endless expression to variety of light and movement, making you lose lines and contours in its fervid glow.”

“There were, of course, other influences at work besides that of Robert Scott Lauder. The Scottish National Gallery, with its superb Van Dycks, Gainsboroughs, and Raeburns, offered endless attractions to the young student, who spent long days there of earnest and concentrated study. The current exhibitions of the Scottish Academy contained works which were a constant stimulus. John Phillip's superb strength and brilliancy of colour must have attracted Pettie, just as it won the life-long allegiance of Chalmers. Phillip's finer work did not begin to find its way to the Edinburgh Exhibition till about 1861, when Pettie's technique was already well formed; but the colour quality of his work, seen in Edinburgh and London during the following years of his maturity, was a spur to the younger painter, who aimed at the same ideal ‘The Hour,’ shown at the Scottish National Exhibition this year (1908), reveals, perhaps, more than any other work by Pettie, an actual resemblance between the two painters. The colour of the somewhat olive face, the full succulent red of the dress, that seems to throw out a radiation of light, the feeling of strength rather than modulation in the handling of solid pigment, all express kinship to the work of Phillip. Both men were master colourists.”

Biography Extracts

“He would argue, too, that Rembrandt's magnificent technique and splendid colour were wasted on his ‘beef-steaks.’ It cannot have been very long before his death that I visited his studio one day to borrow an old silver-mounted pistol. It was to form part of a still-life group to be submitted for some drawing prize at school; and, on his asking how the subject was to be treated, I explained that the pistol was to lie on a Bible with silver clasps, which I had at home. He was instantly up in arms against dulness and convention- ‘I suppose you can't manage & figure? Then why ever don't you put the pistol on a counterpane, with a wisp of smoke coming out of the muzzle, and call it 'The Suicide's Weapon'?’ He could have painted that pistol and book on a tablecloth, and made the dark wood and silver mountings glitter as if they were alive; but the picture to him would have had twice its value with the wisp of smoke and the humped counterpane to tell its tragic tale, to appeal to mind as well as eye.”

“One of the most rapid of workers, he painted in a white heat, sometimes almost a fury, of strenuous effort. He met difficulties or grappled with a new subject with an irresistible dash and cheerfulness, like that of the old British seamen when they came to close quarters and boarded a foeman's ship. His technical achievement of draughtsmanship was of no common order, and his hand was trained to work in quick sympathy with the swiftest perceptions of his brain. In the sense that he saw his subject steadily and saw it whole, that he worked with the rapidity essential for the expression of his first ideas, he was an impressionist in the best and truest sense of the word. He worked directly and unconsciously, not brooding with keen analysis on the scientific placing of his paint, but out of a vivid imagination and exceptional power of mental creation, placing rapidly on the canvas what had taken form in his head. He rarely made sketches or preliminary studies.”

“Working in this way, he retained his freshness right to the completion of each picture, while other artists are often exhausted by preliminary studies and elaborations. And whereas so many pictures of the type which he painted suffer from an extreme of finish and undue stress upon detail, Pettie knew when he had finished and laid aside his brush at the moment when the picture held all its freshness, and when, without a suggestion of labour, every stroke contributed to give it life.”

“He began by laying on paint like water-colour with light brushings in thin transparent tints, giving outlines and dominant notes, and leaving large spaces to be filled later. His advice to a painter of subject-pictures was to begin always with the heads of the principal figures, putting behind them a suggestion of the colour that was required to relieve them. He held that the highest finish should be bestowed upon the central figures, which should fix and fascinate the gaze, summing up and explaining the whole picture, and that there should be nothing in the background to cause momentary distraction. His doctrine was that inherited by Wilkie and the Scottish School from the old Dutchmen, that paint should be thin in the shadows, more opaque in the high lights. ‘Keep your shadows transparent,’ was his advice, ‘and never lose the tooth of your canvas.’”

Obituaries

Aberdeen Evening Express - 22 April 1893

“An act of justice to Pettie's memory, but of considerable heartache to themselves, has just been performed by his executors. They have deliberately destroyed, by cutting them through, some 50 or 60 unfinished studies and ‘ebauches,’ which might later on have got into unscrupulous dealers' hands, and, after the usual custom in some quarters, been touched up and ‘finished’ by hacks, and then launched on the market as genuine ‘Petties.’ The act of destruction is therefore one of pecuniary sacrifice so far as the results of the death-sale are concerned; but the reputation of the artist will certainly gain by it.”